It’s been a minute since I last posted here.

The last time I wrote on this blog was sometime around 2016. A lot has changed since then – in schools, in classrooms, and in how people share their work. I’m not sure blogging is the medium for the moment we’re in anymore.

But I’ve been working on a project I’m very excited about, and I wanted to share it. And maybe writing a blog post like it’s 2014 is exactly the right level of nostalgia I needed. I also enjoy the long form – well, this won’t be long long – more like medium form.

If I talked to the dead and blogged about it, this would be a medium’s medium for medium-sized thoughts.

Wanting to Do Something Different

For the past few years, I’ve been teaching AP World History – a course that covers history from roughly 1200 to the modern-ish day, with a big exam at the end. In addition to content knowledge, students are asked to demonstrate historical thinking skills through a Long Essay Question (LEQ) and a Document-Based Question (DBQ).

The DBQ typically gets introduced during the third unit (November-ish). My usual approach was familiar: introduce the skills, have students practice them in groups, and then collectively look at exemplars released by the College Board. That introduction was already circled in red on my calendar – even though it was still a month away (at least in this retelling; the reality was more of a loose notion of when it should happen). It felt pretty locked in.

One day, before class started, I noticed a student running a science experiment on his computer. He was clicking, testing, watching reactions unfold.

I got a little jealous.

We should have something like that in history.

So I did what any reasonable person would do: I mixed a bunch of fake chemicals together to see what would happen.

Later that night, I kept thinking about it. I started replaying the history games I’d enjoyed over the years. I had joked years earlier about playing Assassin’s Creed Unity (the French Revolution one) in class to teach history. Knowing the history makes that game so much more fun – and some parts a bit easier. My mind drifted…

That’s when my thoughts shifted to one of the biggest set pieces in AP World History: the Document-Based Question, or DBQ. Seven documents. One prompt. An essay built around a rubric made up of discrete skills.

What if that was a game?

And that’s more or less how I stumbled onto the idea.

Why Google Sheets

There is a lot of daylight (and late-night light) between having an idea and actually making something. I took several bites at this apple before settling on Google Sheets – which, in a way, feels like choosing NPR in a world full of streaming platforms. It’s not flashy, but it’s reliable, flexible, and built for depth. [Consider donating to your member stations!]

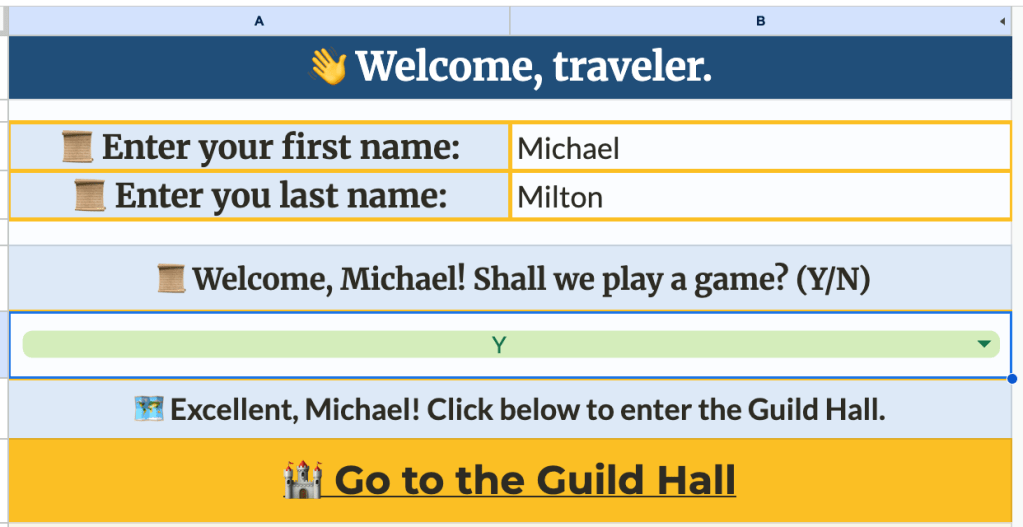

Google Sheets turned out to be the right tool because it let me create interlocking pages and structure the project like a small website rather than a single document. Students could move between quests, dashboards, and feedback without ever leaving the system.

Most importantly, it plays well with Google Classroom. Distribution was simple, permissions were manageable, and everything lived in an ecosystem students already knew. Plus, students’ work saved automatically as they worked their way through the levels.

There were some drawbacks: spellcheck isn’t automatic, and on iPads students need to double-tap to navigate interlinked sheets – which is annoying, but something I walked them through the first time.

Questlines and Levels

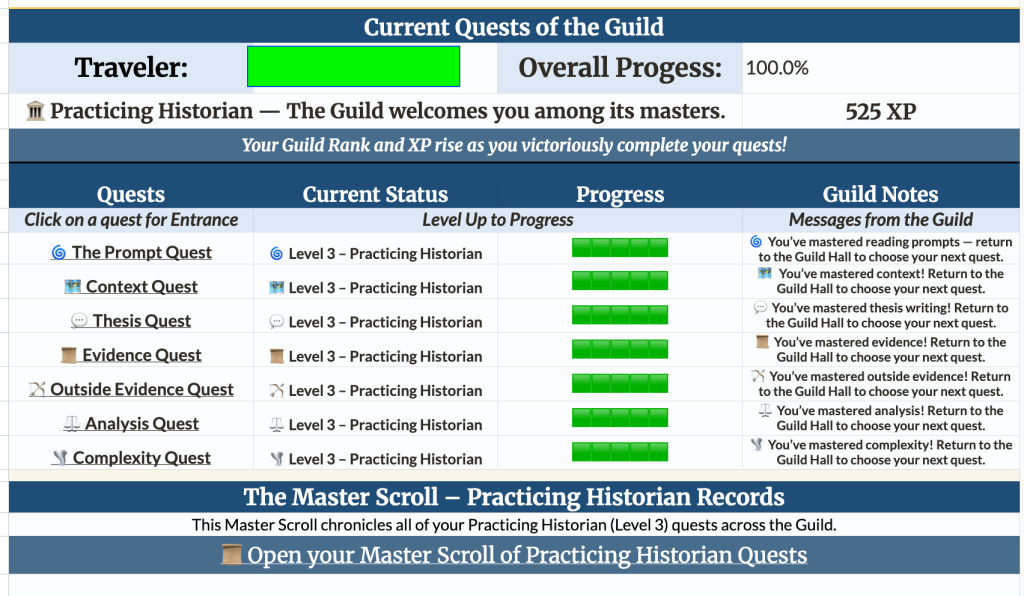

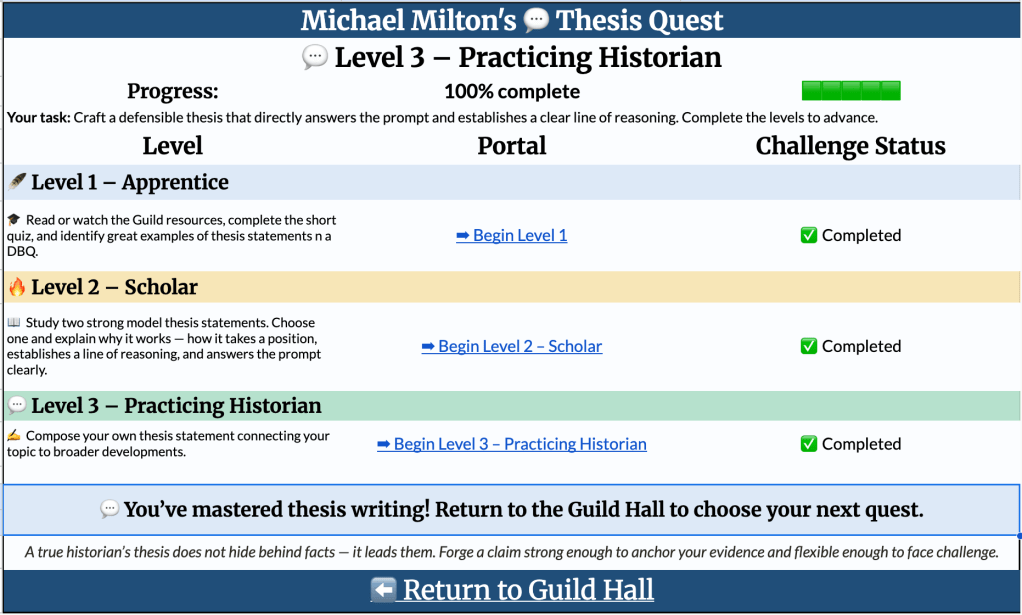

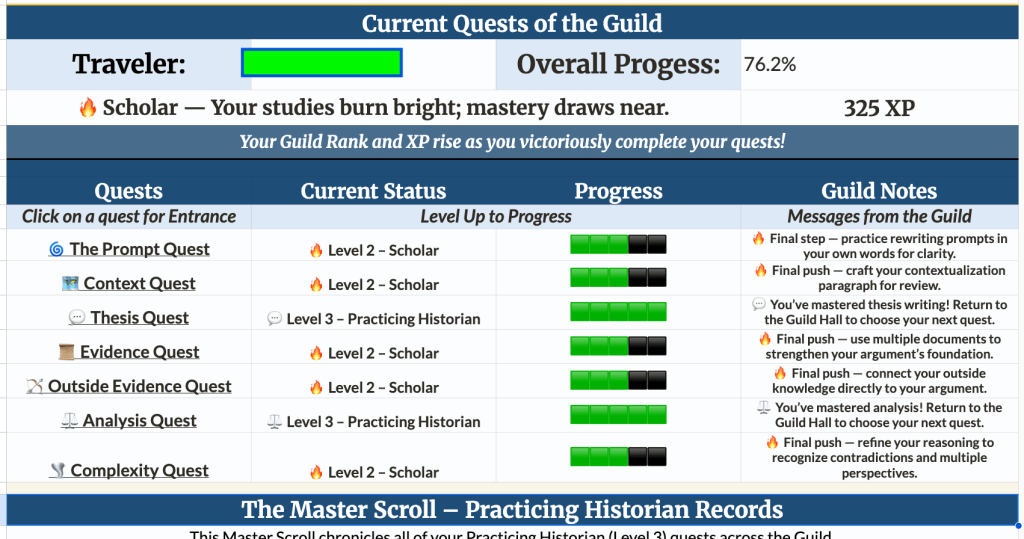

I used the AP DBQ rubric as the foundation for the game, treating each discrete skill in the rubric as its own questline. Once that structure was set, I organized each skill into three levels.

Level One focused on understanding each skill and the AP DBQ rubric itself – what each skill is asking students to do and how it’s evaluated.

Level Two moved from recognition to application. Students analyzed examples of strong responses and then revised a “meh” response to make it better [an idea from a colleague].

Level Three asked students to perform a single, focused task drawn from an actual DBQ. Each level ended with an authentic application rather than a full essay.

At this point, the project had grown to 21 total levels. I made the first level for each skill auto-correcting, but that still left 14 levels where teachers needed to leave feedback and approve student work before students could move forward.

That’s when the problem became clear.

How the heck could anyone manage this?

The idea was cool. I liked the structure of the levels. But how in the world was I supposed to navigate a full class of multi-page Google Sheets and provide timely feedback? I worried this might become one of those ideas I’d try once, admire, and then quietly abandon because it was too complex to sustain.

The Tracker (and Why It Had to Exist)

This was the moment I needed help.

I had already experimented with using ChatGPT to build a basic tracking Google Sheet for student research – comparing submitted research note cards with footnotes (a bud of a project I haven’t fully developed yet). So I leaned into that partnership and started thinking carefully about what the system actually needed to do.

I want to be clear about the role generative AI played here. I’ve never really coded before, and the system I was trying to build was complex. AI didn’t solve the problem for me. It forced me to articulate my thinking more clearly, test ideas, and troubleshoot when things broke. It was often frustrating, but it also extended what I was able to create.

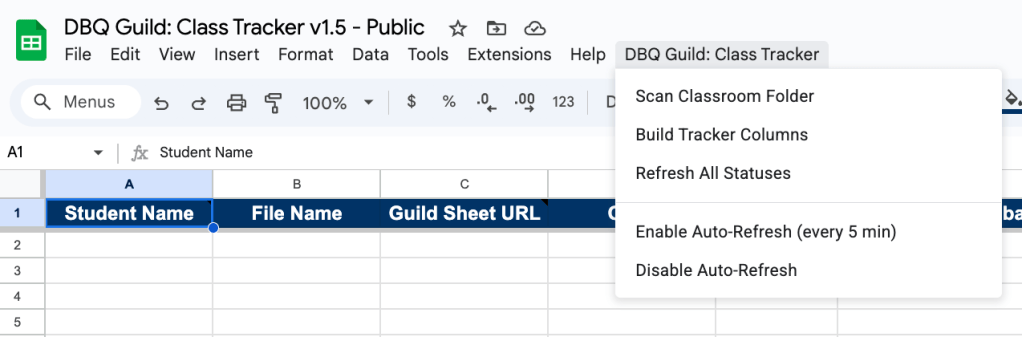

After several rounds of trial and error (currently on version 4.3.1), we built the DBQ Guild Tracker.

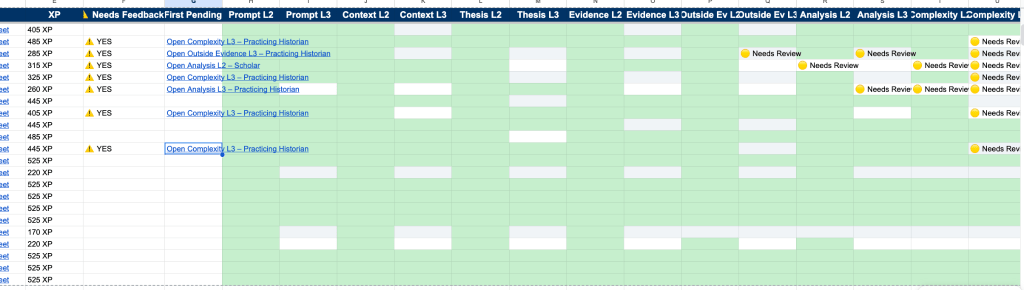

The tracker pulls the URLs of each student’s project directly from the Google Classroom folder that’s automatically created when copies are made. It tracks student progress across quests and flags when a student is ready for feedback. When that happens, it provides a direct link to the exact page that needs review.

That’s what made the project manageable.

After class, I noted:

“The real-time feedback that I am able to give to my students on specific aspects of the DBQ through this setup is so much better than my old method of practice DBQs and having them look at examples – or waiting to see my feedback days later. Students were able to revise and resubmit, sometimes minutes after getting feedback. Plus, I could go talk to students immediately if they were really off track.”

This changed the pace of class entirely.

While students were working, I could jump straight into their project, leave targeted feedback, ask for a revision, or approve the work and move them forward.

It was magic.

What It Looked Like in Practice

After completing the auto-correcting Level Ones for homework, students used class time to work through Levels Two and Three over the next two days. Most students moved through the Level Twos before advancing to Level Threes, which was exactly the point. To unlock Level Three, I needed to approve their Level Two work for that skill.

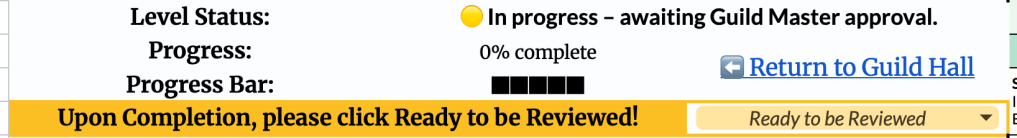

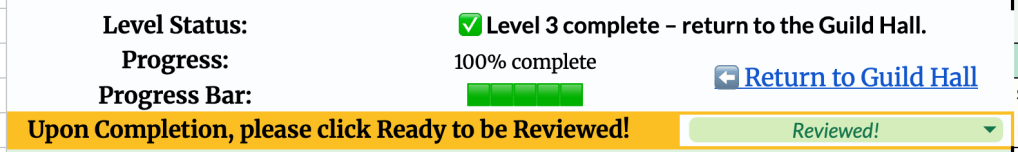

As students worked, I worked. When they completed a level, they marked it as “Ready to be Reviewed,” which the tracker flagged at regular intervals or with a manual refresh. I could immediately see who needed feedback, leave targeted comments, and either approve the work or ask for revisions before moving on to the next student.

Patterns emerged in real time. When the class needed more support with providing context, I could pause and run a quick mini-lesson. When an individual student was struggling, I could walk over and talk with them immediately.

Support didn’t have to wait days like it normally would have. Progress was visible – to students and to me. On my tracker, green meant done. For students, approvals unlocked new levels, and their experience points steadily grew.

Now, it wasn’t all rosy. Students interact directly with the sheets, which means there is the potential to accidentally overwrite cells they shouldn’t. To mitigate this, I used large orange borders to clearly mark the cells students should interact with. I also used Google Sheets permissions so students received a warning if they tried to edit a protected cell. This was a lesson I learned quickly, as my original permissions setup worked differently than I expected and I had to adjust on the fly.

There were also some trust-based decisions. Technically, students could approve their own work. We talked about that openly, and students were respectful about it. More importantly, students were not being graded on individual answers. The focus was on skill development, with revision baked into the system. The goal was to support students as they practiced, revised, and improved.

Collaboration and Iteration

I was very lucky to have a colleague to talk with about this project in the planning phase. One of her ideas directly sparked a Level Two challenge, where students revise a “meh” response instead of only studying polished exemplars. That small shift ended up being one of the most effective parts of the system.

I also received valuable feedback from an AP World History Facebook community, which pushed the project in an important direction. Based on that feedback, I created a single place to house all of the resources tied to each level, along with a dedicated page that collects students’ Level Three work in one spot.

That page opens up an interesting possibility: if teachers want to create a “Level 8 Boss,” students can use that collected work as the foundation for writing their first full DBQ.

Sharing the Project

This project was built specifically for my AP World History students. I initially prototyped it using released AP exam content, but as the project grew, I realized the copyright limitations that come with sharing those materials more widely.

That realization led to some light cursing, followed by a shift to open-source OER DBQs (which brought about much happier cursing). The structure stayed the same – the skills, the levels, and the feedback loop – but the content became far easier for others to adapt and use.

Whenever open-source materials are used, they are clearly credited. Many thanks to OER (www.oerproject.com) for making high-quality, openly licensed DBQs available to teachers.

The Ending

In the classroom, when students finished, we clapped.

Then they noticed a link to a certificate page had appeared.

Hehehe.

Closing Thought

This wasn’t about turning the DBQ into a game. It was about making skill development visible, feedback immediate, and instruction responsive – while students were still thinking.

I really enjoyed making the DBQ Guild. Thinking about these skills in isolation helped sharpen my own understanding of the DBQ, and the creative process itself was genuinely fun. Also tiring. So many roadblocks along the way! But in the end, I am very proud of what I put together.

Lately, I’ve started exploring a smaller-scale follow-up focused on refining a few individual skills. Early experiments suggest some really compelling possibilities – particularly around allowing teachers to make targeted recommendations about which skills specific students should focus on during revision. That work is still taking shape and deserves its own space later on. But that’s a project for another time.

🔗 Project Links

Everything linked below is shared openly so teachers can explore, make copies, and use the materials with their own students. Adapt prompts, tasks, and pacing to fit your classroom.

The Class Tracker includes custom Apps Script code that powers the feedback and progress system. While you are welcome to use the tracker as provided, I ask that the underlying code not be copied, redistributed, or repackaged into derivative tools. The tracker works because the system holds together as a whole.

If you are curious about how something works, want to collaborate, or are thinking about extending the system in a thoughtful way, I’m always happy to talk. More details about setup and Google’s “unverified app” warning are included in the Teacher’s Guide.

If you use it, I’d love to hear how it works in your classroom.

The Project Itself: DBQ Guild ⚔️ Questline 1 v1.5 – Public

The Tracker for the Project: DBQ Guild: Class Tracker v1.5 – Public

A Teacher’s Guide: DBQ Guild ⚔️ Questline 1 – Teacher’s Guide